For most of human history, doctors couldn’t look inside a person without surgery. That all changed in the late 1800s when a German physicist, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, made a surprising discovery. He found a strange type of radiation that could pass through skin and show bones. He called them X-rays.

A Strange Glow in the Lab

For years, scientists had noticed that when they ran electric currents through glass vacuum tubes, the tubes lit up with a bright glow but no one knew why. They didn’t even know about electrons yet.

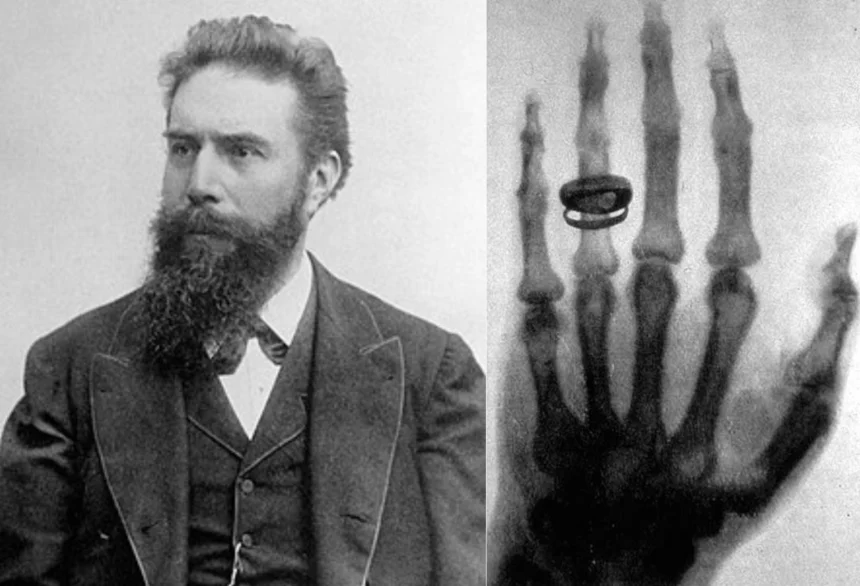

Röntgen, who worked at the University of Würzburg in Germany, wanted answers. On November 8, 1895, he was in his dark lab doing experiments with something called cathode rays.

Suddenly, he saw a glow but not inside the tube. It was shining on a special screen he had placed nearby. A reporter later asked him, “And what did you think?” Röntgen replied, “I did not think; I investigated.”

That moment kicked off weeks of nonstop work. Röntgen locked himself in his lab, barely talking to anyone. He wanted to understand these new rays before telling the world.

Why the Letter “X”?

Röntgen called them X-rays because he didn’t know what they were. In math and science, X is used for something unknown. Anna-Katharina Kätker, deputy museum director of the German Röntgen-Museum, says he worked carefully because “He wanted to be absolutely sure about his discovery.”

She also explains that other scientists had probably created X-rays before but “nobody noticed them.” Röntgen’s work was so detailed that no major new physical facts about X-rays were found until 1912, when Max von Laue discovered they acted like light waves but with much shorter wavelengths.

Röntgen tested all kinds of objects. A 1,000-page book, stacks of cards, tinfoil, wood, rubber—X-rays passed through almost all of them and lit up the screen. Lead was one of the few things that blocked the rays.

One day, he realized the rays went through flesh too. He could see the shadow of his own bones. As a photography fan, he took X-ray photos, including the famous picture of his wife’s hand where you can see her bones and wedding ring.

The World Gets Excited

By late December 1895, Röntgen shared his findings. The reaction was huge. Otto Glasser, who wrote his biography, said, “Rarely in the history of science has information concerning a new discovery or invention been disseminated so rapidly or has it made such a deep impression upon the general public.”

He added that Röntgen’s name reached “the most distant outposts of human culture.”

Not everyone was happy for him. Philipp Lenard, another physicist who later supported the Nazi Party, complained that Röntgen wouldn’t be famous without his earlier work on cathode rays. He hated the name “X-rays” and used “high-frequency rays” instead. But his jealousy didn’t slow anything down.

Other scientists quickly recreated Röntgen’s experiments. Nikola Tesla even took his own X-ray photos. Kätker explains why: “Because experimenting on cathode rays was so popular at the time, almost every physical laboratory had everything you needed to produce X-rays.”

People X-rayed everything—mummies, fossils, weapons. Within months, doctors started using X-rays to find medical problems. This was the birth of radiology. They even used them in wars to help locate bullets in wounded soldiers. Marie Curie later helped bring mobile X-ray units to World War I battlefields.

X-Rays Become Pop Culture

X-rays didn’t stay in labs. They became part of everyday life. In 1896, an English company claimed to sell “X-ray-proof underclothing.” Magazines printed funny cartoons and poems about Röntgen’s discovery. A short film called “The X-Rays” came out in 1897.

By the 1930s, even Superman used X-ray vision in his stories. Shoe stores in the 1930s and 1940s had machines that let customers see the bones in their feet while trying on shoes.

Röntgen won many awards, including the very first Nobel Prize in Physics in 1901. But he didn’t love the spotlight. He agreed to show his discovery to Kaiser Wilhelm II, but he avoided most public events and gave only one interview, to McClure’s Magazine. “I think the press wanted to make him a superstar,” Kätker says, “and he much detested that.”

X-rays led to more breakthroughs. In 1896, a French scientist studying X-rays accidentally discovered radioactivity. In 1897, a British scientist studying X-rays discovered electrons. Those discoveries later helped Albert Einstein explain the photoelectric effect.

According to Kätker, “It was a time of scientists who really were into the invisible.”

The Hidden Dangers

X-rays were amazing but they were also risky. Early users didn’t understand the dangers. People got burns, eye damage, even leukemia.

In 1896, an Austrian doctor used X-rays on a girl’s birthmark and caused an ulcer. A British surgeon lost his hand after long exposure. The German Röntgen Museum even has an amputated hand that shows radiation damage.

In 1904, an assistant of Thomas Edison died from skin cancer caused by X-ray work.

As time passed, people stopped using X-rays for unnecessary things, like shoe fittings. But they’re still important today—in hospitals, dental offices, science labs and airports.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration says most Americans get at least one X-ray each year. The FDA supports using them when needed because the benefit “[It] can even save your life.”