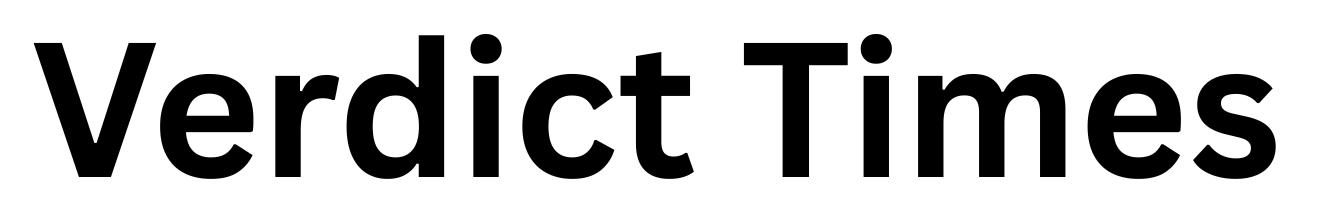

In 1857, a Supreme Court case changed the United States forever. It was about one man, Dred Scott, who wanted freedom for himself and his family. But what started as a simple lawsuit became one of the most controversial moments in American history.

Dred Scott’s Early Life

Dred Scott was born into slavery around 1799 in Virginia. Like many enslaved people, he was moved from place to place by his owners. His first owner, Peter Blow, took him to Alabama and later to St. Louis, Missouri, where he sold Scott to Dr. John Emerson, an Army doctor.

Emerson’s job took him all over. He brought Dred Scott to Illinois, which was a free state and later to the Wisconsin Territory, where slavery was illegal under the Missouri Compromise.

At Fort Snelling in Wisconsin, Dred met and married Harriet Robinson, another enslaved person. Their marriage was performed by Major Lawrence Taliaferro, a justice of the peace and Indian agent. The ceremony mattered because enslaved marriages usually weren’t legally recognized.

Later, Dr. Emerson was sent to Louisiana and then back to Fort Snelling. During that time, Dred and Harriet worked for other people and even earned wages but their pay went straight to Emerson. When Emerson died in 1843, his widow, Irene Emerson, inherited Dred and Harriet.

In 1846, after years of working and living in free areas, Dred Scott tried to buy his family’s freedom. When Irene refused, he decided to fight for it in court.

The First Trial

On April 6, 1846, Dred Scott filed a lawsuit for freedom in the Circuit Court of St. Louis County. His wife Harriet filed one too. It was the first time a married couple in Missouri had filed freedom suits together. They got help from the family of Peter Blow, Dred’s former owner and from lawyer Samuel Mansfield Bay.

Many thought Dred would win easily. Other enslaved people had already won similar cases using the rule, “once free, always free.” But at the trial, a key witness’s words were ruled hearsay, meaning they couldn’t be used as evidence. Because of that, the jury said Dred was still enslaved.

His lawyers didn’t give up. They asked for a new trial — and got one. In 1850, a new jury ruled in Dred Scott’s favor, saying he, his wife, and their children were free. For a moment, it looked like justice had won. But Irene Emerson appealed the case to the Missouri Supreme Court.

In 1852, the Missouri Supreme Court reversed the decision. It said that Dred Scott was still a slave. The judges argued that Missouri didn’t have to follow the laws of other states or territories that banned slavery. One judge wrote, “Every State has the right of determining how far, in a spirit of comity, it will respect the laws of other States.”

This decision broke Missouri’s long rule that living in a free state made a person free. The judges said the times had changed and that Missouri wouldn’t “show the least countenance to any measure which might gratify this spirit.” It was clear that politics and slavery were now tightly tied together.

The Case Goes Federal

By 1853, Dred Scott’s case had drawn national attention. His new lawyer, Roswell Field, worked pro bono — for free — to help him. This time, Dred sued John Sanford, Irene Emerson’s brother, in federal court.

Sanford lived in New York, so the case was allowed under Article III of the U.S. Constitution which let citizens from different states sue each other in federal court.

In 1854, Judge Robert William Wells told the jury to follow Missouri law. Since Missouri had already decided Dred was enslaved, the jury sided with Sanford. Dred appealed again — all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court Steps In

By the time the case reached Washington, the whole country was arguing about slavery. Even President-elect James Buchanan got involved. Before taking office, he wrote to Justice John Catron asking if the Court would decide the case soon.

According to historian Paul Finkelman, “Justice Grier… had kept the President-elect fully informed about the progress of the case and the internal debates within the Court.” Buchanan hoped the ruling would calm things down but it did the opposite.

On March 6, 1857, the Supreme Court announced its decision: Dred Scott lost.

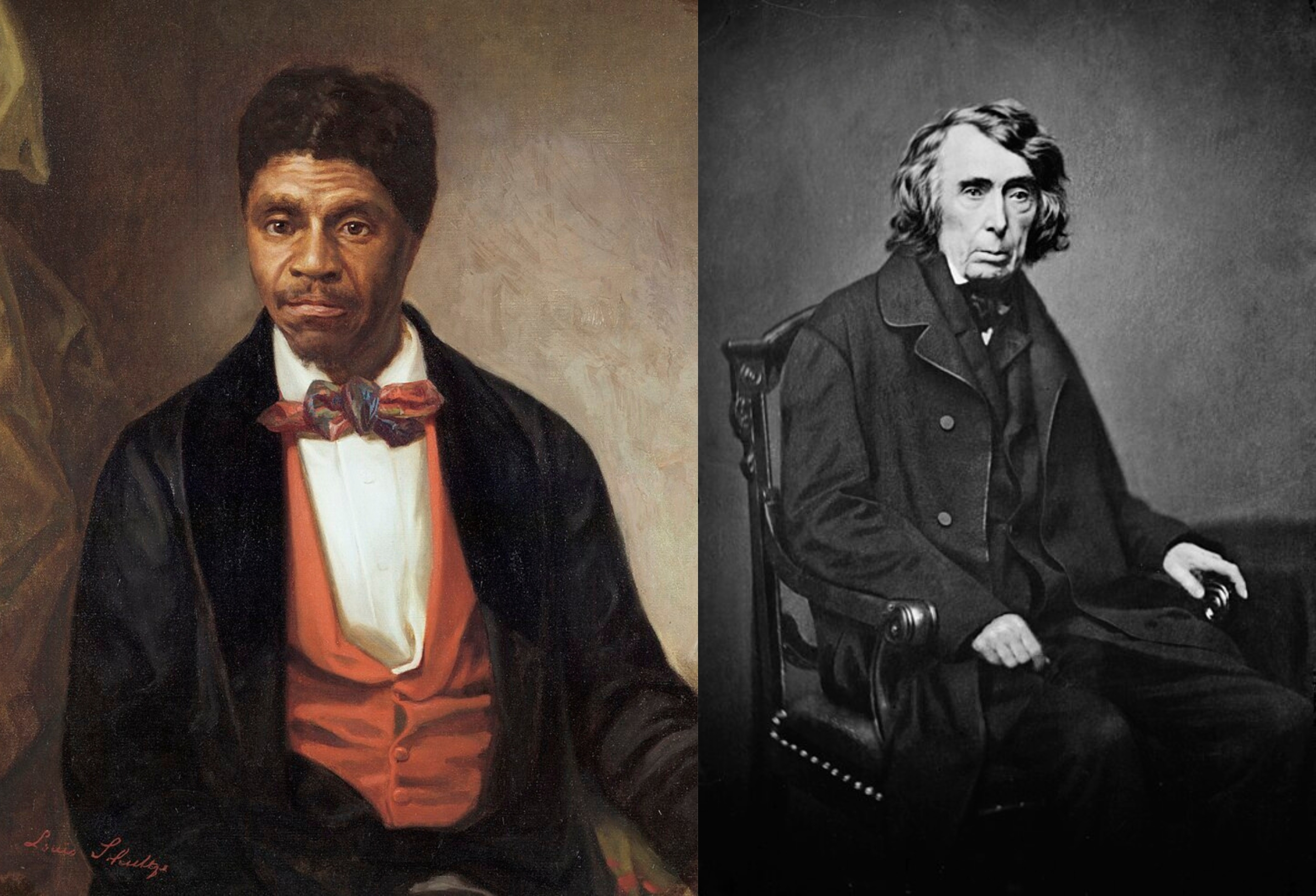

The vote was 7–2, and Chief Justice Roger B. Taney wrote the majority opinion.

He began by asking, “Can a negro, whose ancestors were imported into this country and sold as slaves, become a member of the political community formed and brought into existence by the Constitution of the United States?”

Taney’s answer was no. He wrote that Black people “are not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word ‘citizens’ in the Constitution, and can therefore claim none of the rights and privileges which that instrument provides for and secures to citizens of the United States.”

He also said that African Americans “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”

Taney went even further. He ruled that the Missouri Compromise which had banned slavery in northern territories, was unconstitutional. He said banning slavery violated slave owners’ rights under the Fifth Amendment.

The Dissenting Voices

Not all justices agreed. Two of them — Benjamin Robbins Curtis and John McLean — wrote powerful dissents. Curtis pointed out that when the Constitution was adopted, free Black men could vote in several states, meaning they were citizens.

McLean said the idea that Black people couldn’t be citizens was “more a matter of taste than of law.”

They both said the Court had gone too far. Once the Court decided it had no jurisdiction, it should have stopped there. Instead, Taney’s ruling tried to settle the entire slavery debate and ended up making it worse.

The North was furious. Newspapers attacked Taney’s decision as a “wicked stump speech.” One even said, “If the people obey this decision, they disobey God.”

Republican leaders like Abraham Lincoln saw the ruling as part of a plot to spread slavery everywhere. Lincoln said the Constitution never called enslaved people property — it called them “persons.”

In the South, many celebrated the decision. Jefferson Davis, who would later become President of the Confederacy, said the case showed that the government had no power to interfere with slavery.

Abolitionist Frederick Douglass was outraged but hopeful. He said, “My hopes were never brighter than now. I have no fear that the National Conscience will be put to sleep by such an open, glaring, and scandalous tissue of lies.”

When the Dust Settled

Instead of ending the slavery debate, the Dred Scott case made it worse. It pushed the nation toward the American Civil War. Just a few years later, Lincoln was elected president, Southern states seceded and war began.

After the Union’s victory, the Thirteenth Amendment ended slavery and the Fourteenth Amendment gave citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States.” These laws erased the Dred Scott ruling for good.

Historians later called it the Supreme Court’s biggest mistake. Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes said it was the Court’s “greatest self-inflicted wound.”

Though Dred Scott didn’t live to see the change, his courage helped expose the injustice of slavery.

Sources

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Dred-Scott

https://www.history.com/articles/dred-scott-case

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dred_Scott

https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/dred-waiting-for-the-supreme-court