A homing pigeon named Cher Ami became one of World War I’s most celebrated heroes after delivering crucial messages despite severe battlefield injuries.

From English Loft to French Battlefields

Cher Ami, which means “dear friend” in French, was born in late March or early April of 1918 in England. He had a band on his leg that said “NURP 18 EAD 615,” which showed he was a National Union Racing Pigeon, probably from E. A. Davidson’s loft in Norfolk. This young pigeon had no clue he was about to end up in one of the deadliest wars in history.

Homing pigeons had served as messengers for thousands of years, relying on their remarkable ability to navigate back home. When World War I erupted, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom already had established pigeon messenger services. The United States, however, was late to recognize their value. The U.S. Army had experimented with pigeon messengers in 1878 with success but failed again in 1916.

Everything changed when American forces arrived in France. British and French allies quickly informed Colonel Edgar Russel, General John Pershing’s chief signal officer, about the advantages these birds offered on the battlefield. Convinced of their usefulness, General Pershing requested the establishment of the U.S. Army Signal Corps’ Pigeon Service in November 1917.

On May 20, 1918, the British donated 600 English-bred pigeons to the American Pigeon Service. Cher Ami was among them. Three days later, the birds arrived in Langres, France, where 245 were selected and sent directly to the front lines.

These pigeons served as a communication method of last resort for troops in dangerous positions. Soldiers would write messages three times on thin paper, place them in a small canister attached to the bird, and release the pigeon to fly back to its loft where handlers would read the message.

Cher Ami was assigned to Mobile Loft No. 11, managed by Ernest Kockler. On September 21, 1918, the loft relocated to Rampont, France, preparing to support the massive Meuse-Argonne Offensive. The birds of Mobile Loft No. 11 would support the 77th Infantry Division as they pushed through the dense Argonne Forest.

The Lost Battalion’s Desperate Situation

On October 2, 1918, Major Charles W. Whittlesey led the first battalion of the 77th Infantry Division into the Argonne Forest. Captain George G. McMurtry commanded the second battalion alongside him, and two companies of the 306th Machine Gun Battalion accompanied them. The soldiers carried eight pigeons for emergency communication. The group advanced into the Charlevaux Ravine and established their position there.

The following day, Captain Nelson M. Holderman arrived with Company K of the 307th Infantry Regiment, bringing their total strength to approximately 554 men. Around nine o’clock that morning, soldiers released two pigeons requesting artillery support. Unfortunately, one message contained incorrect coordinates.

Shortly after, German forces completely cut off the American runners who normally carried messages between units. The battalion found itself trapped in the ravine with enemies surrounding them on all sides.

The situation grew increasingly desperate. The men had exhausted their food rations and possessed only limited medical supplies. By this point, they had already lost about a quarter of their force to casualties. Two more pigeons were sent out explaining their dire circumstances.

On the morning of October 4, Whittlesey dispatched another pigeon asking for help. The Germans intensified their assault with mortars and gunfire throughout the morning. A sixth pigeon was released as conditions worsened. Then, at 2:30 in the afternoon, the 305th Field Artillery Regiment began firing on a slope near the American position.

The artillery crews meant to protect Whittlesey’s men, believing the battalion occupied the southern slope of the ravine. In reality, the Americans held the northern slope. The protective barrage became a devastating friendly fire incident, with American shells raining down on American soldiers.

The shelling continued for approximately thirty minutes. Whittlesey desperately needed to communicate with headquarters to stop the artillery assault. He grabbed a piece of paper and wrote a frantic message: “We are along the road paralell 276.4. Our artillery is dropping a barrage directly on us. For heavens sake stop it.”

Cher Ami Takes Flight

Private Omer Richards received the urgent note from Major Whittlesey. He placed the message in a small capsule and reached into his pigeon basket. Only two birds remained. A nearby shell explosion startled Richards and the first pigeon, which escaped before the message could be attached. Richards then took the last pigeon, believed to be Cher Ami, and tied the message to the bird’s right leg before releasing him into the smoke-filled air.

Cher Ami did not immediately fly toward headquarters. Instead, he landed on a nearby branch just a short distance away. The desperate soldiers tried shooing the bird onward, waving their arms and shouting. The pigeon refused to budge. Finally, Richards climbed the tree himself and shook the branch until Cher Ami took flight again.

As the pigeon rose above the brush, German soldiers spotted him against the sky. They opened fire immediately, knowing that shooting down messenger pigeons could doom trapped American units. Bullets struck Cher Ami, and he tumbled from the sky. Remarkably, the wounded bird managed to take flight once more and continued toward his loft at division headquarters.

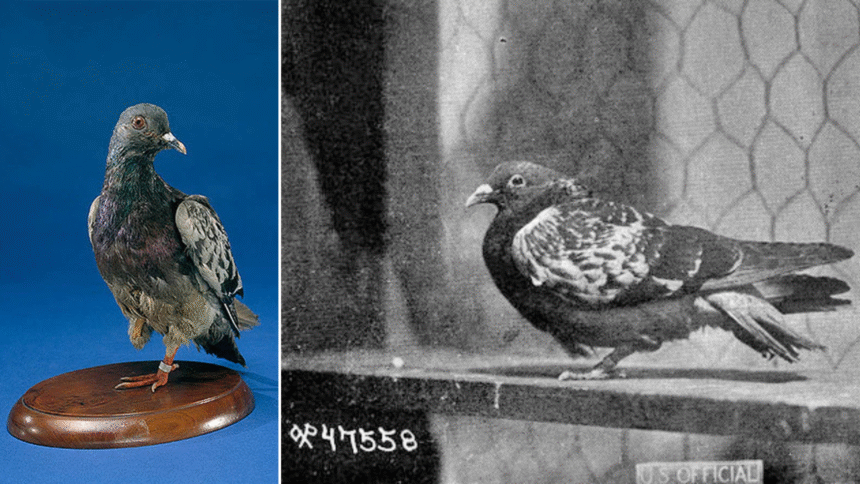

Cher Ami covered the 25-mile distance back to Rampont in just 25 minutes, arriving approximately five minutes after the friendly fire shelling had finally ceased. He arrived severely wounded, shot through the breast with his right leg nearly destroyed. The message capsule dangled from what remained of his leg, held only by ligaments. Army medics immediately went to work trying to save the bird’s life.

The men trapped in the ravine endured several more days before rescue finally came. Only 194 of the original 554 soldiers walked out of the forest on their own feet. They became known forever as the Lost Battalion, and Cher Ami became their legendary savior. The 77th Infantry Division celebrated the pigeon as their hero.

Recognition and Lasting Mystery

After recovering from his wounds, the now one-legged Cher Ami prepared for his journey home. General John J. Pershing himself came to see the bird off. On April 16, 1919, Cher Ami arrived in the United States aboard the ship Ohioan, having stayed in Captain John L. Carney’s cabin during the voyage. When Carney spoke to reporters at the dock, his statements became the foundation of the Cher Ami legend, directly crediting the pigeon with rescuing the Lost Battalion.

The story spread rapidly through newspapers across the country. Carney attended numerous press events featuring the famous bird. Afterward, Cher Ami was housed at a loft in Potomac Park in Washington, D.C. France awarded him the Croix de Guerre Medal with a palm Oak Leaf Cluster for delivering twelve important messages at Verdun. He later received a gold medal from the Organized Bodies of American Racing Pigeon Fanciers.

However, questions about the exact nature of Cher Ami’s service emerged over time. According to Frank A. Blazich Jr., curator of modern military history at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History, no conclusive evidence directly links Cher Ami to the Lost Battalion action.

Official Signal Corps records indicated the bird was wounded flying from Grandpré on October 21 or 27, not from the Charlevaux Ravine on October 4. The Army may have chosen to connect Cher Ami with the famous Lost Battalion story to promote the Signal Corps’ Pigeon Service.

Cher Ami died at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, on June 13, 1919, from his battle wounds. The Army Signal Corps donated his remains to the Smithsonian Institution, where taxidermist Nelson R. Wood prepared him for display. When the Smithsonian requested service records, the Signal Corps admitted they could find no documentation proving Cher Ami carried the Lost Battalion message.

In 2021, DNA analysis confirmed Cher Ami was male. He was inducted into the Racing Pigeon Hall of Fame in 1931 and received the Animals in War and Peace Medal of Bravery posthumously in November 2019. Today, visitors can see Cher Ami displayed at the National Museum of American History exhibit titled “The Price of Freedom: Americans at War.”