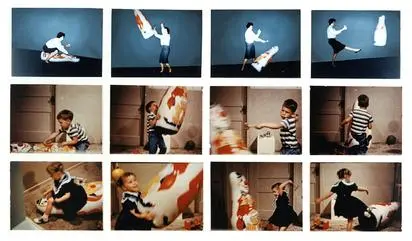

Back in the early 1960s, a psychologist named Albert Bandura wanted to know something simple but powerful. Do kids learn how to behave just by watching other people? To find out, he used an inflatable clown toy called a Bobo doll.

Between 1961 and 1963, Bandura ran a series of experiments to test his social learning theory which said that people can learn new behaviors by observing, imitating and modeling others — not just through direct rewards or punishments.

In one of his most famous lines, Bandura explained, “Kids who saw an adult hitting a Bobo doll were more likely to imitate that aggression.”

The First Experiment (1961)

In 1961, Bandura and his team worked with 72 children from the Stanford University nursery school. They were all between 37 and 69 months old — so, basically preschoolers.

The kids were split into three groups. One group watched an adult acting aggressively with the Bobo doll. Another saw a non-aggressive adult quietly playing with other toys. The last group was the control group which didn’t see any adult model at all.

Each child took part alone to make sure classmates didn’t influence them. The playroom had two corners. One for the child, filled with fun things like stickers and stamps and one for the adult, with a toy set, a mallet and the Bobo doll.

Before leaving, the experimenter told the child that only the adult could play with the toys in the adult’s corner.

Then the real show began.

In the aggressive scenario, the adult started attacking the Bobo doll — hitting it, punching it and even smacking it with the mallet. The adult shouted things like “Sock him!” and “Pow!” as the Bobo doll bounced around. After ten minutes, the adult left and the child was taken to another room.

In the non-aggressive version, the adult just played calmly with other toys, completely ignoring the Bobo doll.

After that, each child was moved to another room full of cool toys like trucks and dolls. But just as they started playing, the experimenter told them they couldn’t play with those toys anymore because they were “for other children.” The goal was to make them frustrated.

Then the kids were led into a room full of “aggressive” toys, including the famous Bobo doll and the mallet — and told to play freely for 20 minutes. Meanwhile, researchers quietly watched and took notes.

They measured four things:

- Physical aggression (like punching or kicking the doll)

- Verbal aggression (repeating the angry phrases the adults had used)

- Other forms of aggression using the mallet

- New aggressive actions that weren’t shown by the adult model

What Bandura Found

The results were clear. Kids who watched the aggressive adult were way more likely to hit or yell at the Bobo doll than those who hadn’t seen it happen.

Gender also made a difference. Boys were more aggressive overall, especially when they saw a male model being violent. Girls were less likely to imitate aggression but they still did it when they saw a woman acting that way.

Bandura also noticed that kids who watched calm adults were less aggressive than even the control group — meaning that seeing someone stay calm might make children calmer, too.

In total, when researchers counted up every act of aggression, boys showed 270 while girls showed 128.

The 1963 Study: Watching It on TV

Two years later, Bandura wanted to know if kids would still imitate aggression if they saw it on film or in a cartoon instead of in real life.

So in 1963, 96 children — half boys, half girls — were split into three groups.

- One group saw a live model being aggressive toward a Bobo doll.

- Another watched a movie of a person doing the same thing.

- The last group watched a cartoon cat attack the doll.

After watching, each child was again put through a mild frustration test and then allowed to play with toys, including the Bobo doll and the “weapons.”

The results were almost the same as before. Kids who saw aggression, whether in person, on film or in a cartoon were more likely to copy it. It didn’t matter if the model was real or animated.

Bandura found no evidence that watching violent behavior helps “release” aggressive feelings, a theory called the cathartic effect. Instead, it seemed to make kids more likely to be aggressive.

This part of his research became especially important later on, as people debated whether violent TV shows and movies make kids more aggressive.

The 1965 Study: Rewards and Punishments

For his final version in 1965, Bandura wanted to know if kids would act differently after seeing the model get rewarded or punished for being aggressive.

He worked with 66 children — 33 boys and 33 girls. One group saw an adult hit the Bobo doll and then get praised and given candy. Another group saw the same scene but the adult was scolded and hit with a small golf club. The third group was the control where nothing happened to the adult afterward.

After watching, each child was put in a playroom for ten minutes and researchers counted every aggressive act. Then they repeated the experiment, this time offering kids rewards like candy, juice and stickers if they copied what they saw.

The outcome was kids in the punishment group showed less aggression, especially girls — while the reward and control groups acted about the same. But once kids were promised rewards for imitating, all three groups showed more aggression.

Bandura concluded that rewards and punishments don’t stop kids from learning the aggressive behavior. They only affect whether or not the kids choose to show it.

What the Experiments Proved

All of these studies supported Bandura’s social learning theory — that people can learn behaviors by simply watching others.

He showed that role models matter, especially if they are admired. When children saw adults get praised for hitting the Bobo doll, they copied it. When the adults were punished, the kids backed off.

This process is called vicarious reinforcement, meaning people learn by seeing someone else get rewarded or punished.

The Bobo Doll experiments helped explain how media violence, parenting styles and peer behavior can all shape how kids act.

Criticism of the Bobo Doll Experiments

Even though Bandura’s work was a huge deal in psychology, it definitely wasn’t flawless. Some experts argued that the experiments had low ecological validity, meaning the setup didn’t feel real enough.

In real life, kids actually know the adults they watch — like parents or teachers but in this study, the model and the child were total strangers who never even talked or interacted.

Others pointed out that while the Bobo study might not reflect real life perfectly, it has still been useful in workplaces and schools to understand how aggression spreads.

A 1990 repeat of the experiment found something interesting. Kids who had never seen a Bobo doll before were five times more likely to copy aggression than those who had. Researchers suggested that the novelty of the doll itself might make kids hit it more.

Some scientists also argued that Bandura’s theory ignored biology — like brain development, hormones or genetics which could also affect aggression.

Ethics were another big concern. The kids couldn’t give consent, might have learned aggressive habits, weren’t given a chance to withdraw and were never debriefed after the experiment.

Later research by Bar-on et al. (2001) added that children under eight have underdeveloped frontal lobes, making it harder for them to tell fantasy from reality. That means some kids might not even realize the adults’ behavior wasn’t okay.

Finally, psychologists noted that Bandura’s study only looked at short-term reactions. Since the kids imitated aggression almost right after seeing it, no one could say if those effects lasted in the long run.

Sources

https://www.britannica.com/event/Bobo-doll-experiment

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bobo_doll_experiment

https://www.verywellmind.com/bobo-doll-experiment-2794993

https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/health-and-medicine/bobo-doll-experiment