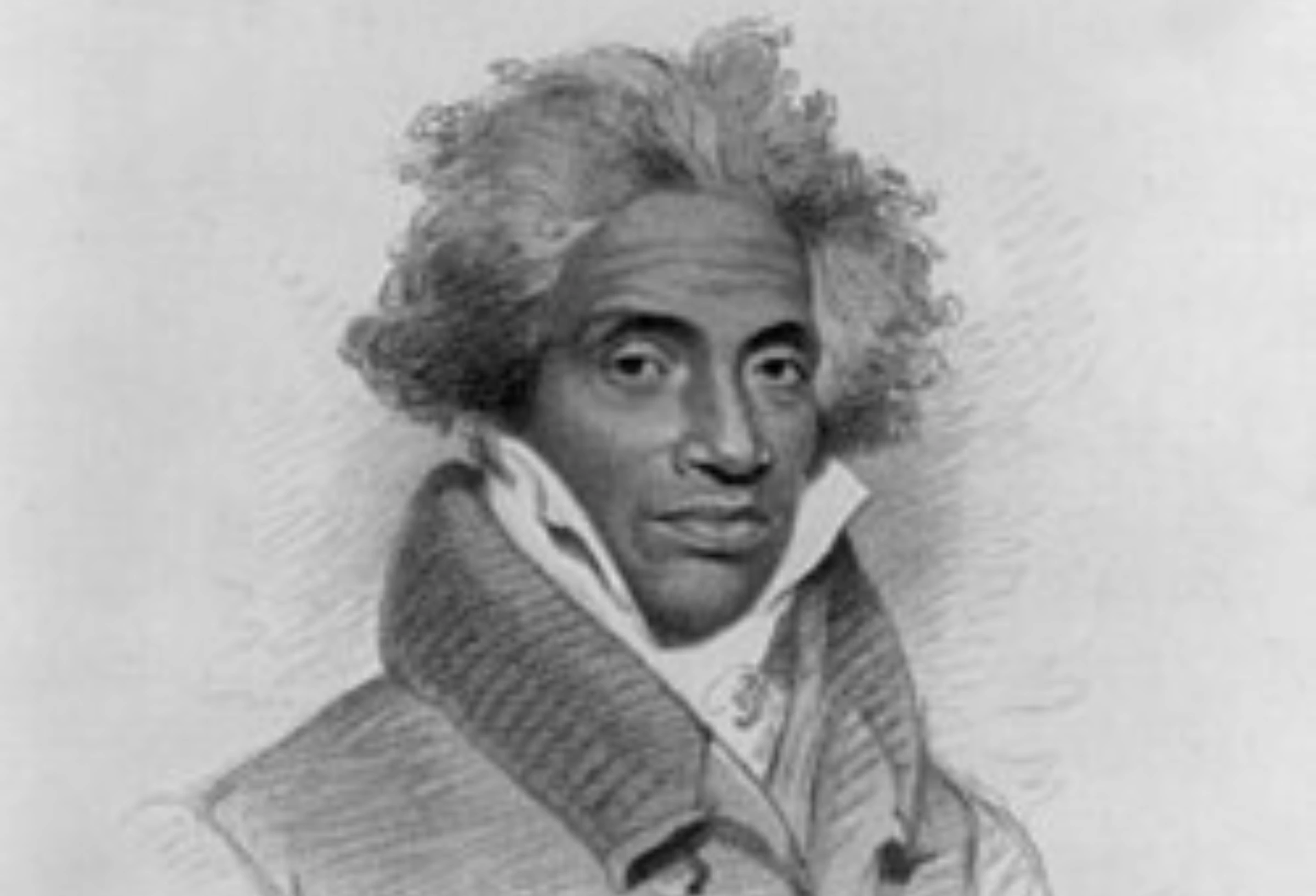

Back in the late 1700s, a young prince from West Africa’s Fouta Djallon region got captured and sold into slavery. His name was Abdul Rahman Ibrahima ibn Sori. Born in 1762, Abdul Rahman was a Fula prince and an Amir (commander) from Guinea.

A Prince from Fouta Djallon

Abdul Rahman was born into privilege. His father, Ibrahima Sori, was the powerful ruler of Fouta Djallon, a region in what is now Guinea. His mother was a Moorish woman.

When Abdul Rahman was only five, his family moved from Timbuktu to Timbo, which later became the capital of his father’s Islamic state.

He received an excellent education. He studied in madrasahs (Islamic schools) at Djenné and Timbuktu and spoke several languages — Bambara, Fula, Mandinka, Yalunka and of course, Arabic.

By 1781, he returned home and joined his father’s army. He quickly became a skilled commander and was later made an Amir, or regimental leader.

Captured and Sold into Slavery

In 1788, everything changed. Abdul Rahman was leading 2,000 cavalry troops in a campaign against a local group called the “Hebohs.” Although he won the first battle, his troops were later ambushed in the mountains. Refusing to run away, he was shot, captured and enslaved.

He was taken to the Gambia River and sold to slave traders for what was said to be “two bottles of rum, eight hands of tobacco, two flasks of powder and a few muskets.”

From there, he was shipped to Dominica and then to New Orleans, before being taken upriver to Natchez, Mississippi. There, a man named Thomas Foster bought him for about $950.

Life on the Foster Plantation

Abdul Rahman wasn’t used to being treated like a slave. In his culture, fieldwork was done by women or servants, not by noblemen. He refused to work and was whipped many times. Eventually, he escaped and hid in the woods for weeks. But with nowhere to go, he decided to return to Foster’s plantation and accept his fate.

On Christmas Day, 1794, Abdul Rahman married Isabella, another enslaved woman on the plantation. Together they had nine children.

Though Isabella joined the Baptist Church in 1797, Abdul Rahman stayed true to his Muslim faith, attending services but disagreeing with Christian teachings like the Trinity. He also criticized how Christianity was used to justify slavery.

Despite his situation, he became respected on the plantation. He was intelligent, trustworthy and skilled at managing cattle and crops. Because of this, Foster often let him go to Washington, Mississippi, to sell vegetables at the market.

An Unexpected Reunion

In 1807, while at the market, Abdul Rahman ran into someone unexpected — Dr. John Coates Cox, an English surgeon. Years earlier, Cox had been stranded and injured on the West African coast and was rescued by Abdul Rahman’s family. He had even lived in their household for six months before returning home.

Now, decades later, Cox recognized the man selling vegetables as the prince who once helped him. Shocked, Cox offered Foster $1000 to buy Abdul Rahman’s freedom. Even the governor of Mississippi supported him. But Foster refused. He said Abdul Rahman was too valuable to his plantation.

Cox never gave up but he died in 1816 without success. Later, his son William Rousseau Cox also tried to free Abdul Rahman but was turned down too.

The Letter That Changed Everything

In 1826, with the help of a newspaperman named Andrew Marschalk, Abdul Rahman wrote a letter in Arabic to his family back in Africa. The letter was sent through U.S. Senator Thomas Reed to the American Consulate in Morocco where it reached Sultan Abd’ al Rahman II.

The Sultan, realizing who Abdul Rahman was, asked U.S. President John Quincy Adams and Secretary of State Henry Clay to help free him — offering to release some Americans in Morocco in exchange.

In 1828, after forty years in slavery, Foster finally agreed to free him, giving him to the Marschalk family, who officially manumitted (freed) him. The deal was that he would be sent to Africa by the U.S. government. Citizens in Natchez also helped raise $200 to free Isabella.

After gaining his freedom, Abdul Rahman and Isabella traveled to Baltimore, where he met Henry Clay and then to Washington, D.C., where he met President John Quincy Adams on May 15, 1828.

He told the President he wanted to free his five sons and eight grandchildren still enslaved in Mississippi. He even wrote them a heartfelt letter about the meeting.

A Tour for Freedom

Before leaving America, Abdul Rahman and Isabella spent 10 months traveling through northern cities to raise money. They spoke to newspapers, politicians and the American Colonization Society, all to help buy their family’s freedom.

He dressed in Moorish clothing to stand out and appealed to different audiences: merchants, missionaries and abolitionists.

He even worked with Rev. Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, a well-known educator for the deaf. But his activism angered both Foster and Marschalk, who felt betrayed. Marschalk went as far as publishing negative articles about him and President Adams during the election.

When it was time to go, the couple had raised only $4000 — not enough to free all their family. Still, they left Norfolk, Virginia, on February 9, 1829, aboard the ship Harriet, traveling to Liberia with other freed people under the American Colonization Society program.

A Bittersweet Return to Africa

After arriving in Liberia, Abdul Rahman wrote letters back to America, saying he planned to trade with his homeland and was trying to get more funds to free his family. But his health was failing.

Reports say that although he had acted like a Christian to gain support in America, he returned fully to Islam “as soon as he got in sight of Africa.”

Sadly, just a few months later, a yellow fever epidemic swept through the area. Abdul Rahman died on July 6, 1829, at about 67 years old — never making it back to Fouta Djallon or seeing his children again.

After his death, Isabella managed to free and reunite with only two of their sons and their families in Monrovia. The rest of their children stayed enslaved under Foster’s heirs after his death the same year.

Abdul Rahman’s incredible story of courage and dignity was later retold in “Prince Among Slaves,” a book by Terry Alford and a PBS film directed by Andrea Kalin, narrated by Mos Def.

Sources

https://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/maai/freedom/text1/ibrahima.pdf

https://www.blackhistoryheroes.com/2011/03/abd-al-rahman-ibrahima-ibn-sori-from.html

https://www.history.com/articles/african-prince-slavery-abdulrahman-ibrahim-ibn-sori