Back in 1920, two researchers at Johns Hopkins University — John B. Watson and his student Rosalie Rayner — ran a strange experiment. They wanted to see if a baby could be taught to be scared of something. The study, known as The Little Albert experiment, later became one of psychology’s most talked-about (and criticized) cases.

Setting the Stage

Watson had noticed that babies often cried when they heard loud noises. He believed that this fear of noise was natural, something babies were born with. But what if you could make a baby fear something totally harmless, like a white rat, by pairing it with a scary sound?

So, Watson picked a nine-month-old baby boy who was nicknamed “Albert.” Before the experiment, Albert was shown different things — a white rat, a rabbit, a dog, a monkey, masks, wool and even burning newspapers. He didn’t cry or show any fear.

Then, when Albert turned 11 months old, the real experiment began.

How the Experiment Worked

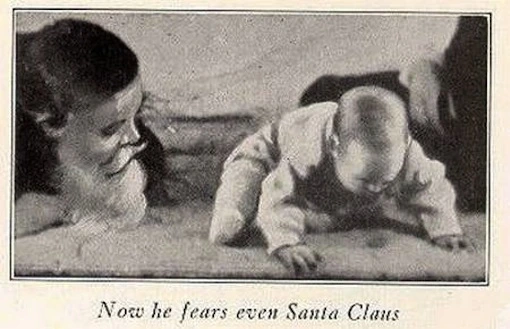

Albert was placed on a small mattress in the middle of a room. A white rat was let loose near him and he reached out to touch it. That’s when Watson made a loud, clanging sound by hitting a steel bar with a hammer right behind Albert. The sudden noise scared the baby. He cried and turned away.

Watson and Rayner repeated this a few times. Eventually, just seeing the rat made Albert upset. The white rat which had been a “neutral” thing before, became something he was afraid of.

The loud sound (called the “unconditioned stimulus”) made Albert cry (the “unconditioned response”). But now, the rat alone made him cry — that was the “conditioned response.”

Soon, Albert seemed to fear other fuzzy things too — a rabbit, a furry dog, a fur coat and even a Santa Claus mask with cotton balls for a beard. But not everything with hair scared him, so the generalization wasn’t perfect.

By today’s standards, the study was full of problems. It only had one subject — Albert — and there were no controls or follow-up tests. Plus, modern rules for protecting people in research didn’t exist yet. Today, this kind of experiment wouldn’t be allowed at all.

Watson himself admitted the fear they created wasn’t very strong or long-lasting. Albert left the hospital shortly after the experiment ended and Watson never tried to help him “unlearn” the fear.

What Happened Next

Even though the experiment was short, it made a big impact. Watson gave lectures about it and one of his students, Mary Cover Jones, got inspired to do her own research.

She worked with a young boy named Peter, who was terrified of rabbits. To help him out, Mary started showing him the rabbit little by little while he hung out with other kids who weren’t scared at all. Bit by bit, Peter got used to it and before long, his fear completely disappeared.

Mary Cover Jones became known as the “Mother of Behavior Therapy.” Watson even helped edit her study, showing how the Little Albert experiment indirectly led to more humane psychological methods.

The Mystery of “Little Albert”

For years, no one knew who “Albert” really was. Textbooks claimed that his mother worked in the same hospital as Watson and took her baby away once she learned what happened. But this story was later challenged.

In 2009, psychologists Hall P. Beck and Sharman Levinson looked into Watson’s letters, census records and other documents. They believed Albert was actually a baby named Douglas Merritte, the son of a hospital nurse named Arvilla Merritte.

Douglas had a serious brain condition called hydrocephalus — an accumulation of fluid in the brain — and sadly died at age 6. If Douglas really was Albert, that meant Watson’s claim that the baby was “healthy” wasn’t true.

Researchers later noticed that in the experiment’s film, the baby used odd hand movements and didn’t show normal eye focus or facial reactions — signs that matched Merritte’s medical condition.

But not everyone agreed. Other researchers — Russ Powell, Nancy Digdon, and Ben Harris — thought “Albert” was actually Albert Barger, another baby from the same hospital who was born a day apart from Douglas.

The Case for Albert Barger

Powell and his team pointed out that Barger’s development matched the notes from Watson’s study. They even checked medical files and found Douglas Merritte had been “completely blind,” which didn’t fit the film of Little Albert clearly watching and reacting to objects.

Barger also left the hospital at exactly 12 months and 21 days old. The same age Watson recorded for the baby’s last day in the experiment.

A genealogist later helped confirm more details. Barger had lived a long life, passing away in 2007 at age 87. When researchers spoke to his niece, she mentioned that her uncle didn’t like animals, especially dogs.

The family sometimes teased him about it. She didn’t think it was a major fear but it was enough that people would put their pets away when he visited.

The researchers concluded that Barger probably never knew he’d been part of such a famous experiment.

Why It Wouldn’t Be Allowed Today

If someone tried to repeat the Little Albert experiment now, they’d run into serious ethical problems. The American Psychological Association (APA) and U.S. laws now protect human research subjects.

In the 1970s, after several controversial studies, the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research was formed. In 1979, it released The Belmont Report which became the foundation for modern research ethics.

Under these rules, Watson’s experiment wouldn’t pass review. It caused emotional distress, had no informed consent and didn’t attempt to reverse the harm. Since 2000, researchers funded by the National Institutes of Health must be trained in handling human participants safely.

Experts Speak Out

Not everyone has kind words for Watson’s work. Psychologist Ben Harris reviewed the original study in 1979 and wrote: “Critical reading of Watson and Rayner’s (1920) report reveals little evidence either that Albert developed a rat phobia or even that animals consistently evoked his fear (or anxiety) during Watson and Rayner’s experiment.”

He added that while the study inspired later research, it should be seen as “interesting but uninterpretable.”

In other words, there’s no solid proof that Albert’s fear lasted or that he truly became phobic.

One major criticism is that Watson’s claim that Albert was a “healthy” child may not have been true, at least if he was Douglas Merritte. Some say Watson and Rayner knew the baby was very ill but still used him as if he were typical. Critics have even called that academic dishonesty.

However, this claim was challenged. Articles later published in the same scientific journals argued that Albert wasn’t Merritte but William “Albert” Barger — a healthy baby. These researchers said that the “sick baby” story was wrong.

Sources

https://www.verywellmind.com/the-little-albert-experiment-2794994

https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/psychology/little-albert-study

https://science.howstuffworks.com/life/inside-the-mind/emotions/little-albert-experiment.htm